Alofs, the best-selling author of the business book Passion Capitol, told Samaritanmag he doesn’t even consider himself a fundraiser. Now 61, he had spent a good deal of his adult life in the music industry, becoming president of music retail chain HMV in 1989 at the age of 33. He hadn’t worked his way up, as is commonplace in the music biz. He didn’t even have a background in the music industry, let alone play in a band. He was plucked from Marketing and Promotion Group. The only retail experience he had was working in a beer store, way back when. But how could he not be a music fan growing up in Windsor, Ontario, listening to CKLW, the legendary top 40 radio station which also served Detroit?

He helmed HMV Canada from 1989 to 1995, leading its growth from $30 million annual sales to over $200 million. He then became president of BMG Canada for two years until 1997, when he accepted a position in Los Angeles with Disney Stores North America, overseeing 500 locations. In 1999, he briefly ran online music site MP3.com, then returned to Toronto as a private investor. He soon learned that his mother, Patricia, had cancer, and along with his siblings became her caregiver until her death in 2002. The difficult experience left him with “a burning desire and passion to try and do something important for cancer.”

He spent a month volunteering at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in 2003, then dove into his role as president and CEO. The torch has now been passed to Michael Burns, who has big — and active — shoes to fill. Alofs not only spearheaded the 200km Ride to Conquer Cancer and Road Hockey To Conquer Cancer but participated in them.

Alofs spoke to Samaritanmag at one of his last days in his office, touching on his accomplishments, the research centre’s breakthroughs, parallels with the music industry, and what’s cooler, a bobblehead in his likeness or an area of the hospital bearing his name.

I want to start with what you’ve seen over these 14 years in terms of the research and progress because it can be disheartening on the outside. We all know people who have got cancer, either beaten it or died from it. There are so many fundraisers to find a cure. What have you found encouraging?

The basic statistic that is so discouraging is that 1 in 2 Canadians [according to the Canadian Cancer Society], or 1 in 2 North Americans, will face a cancer diagnosis in their lifetime. That’s up from 40 percent. So more of us will be getting diagnosed. The encouraging part is in 1970, the statistic was 25 percent of people diagnosed with cancer would live 10 years or longer; now it’s 50 percent of people diagnosed with cancer will live 10 years or longer. For example, breast cancer, especially when it’s diagnosed early, is almost 90 percent curable. There are other cancers that are almost curable at this point. There’s been a lot of progress, but cancer’s still the leading cause of death in North America. That’s likely not going to change.

Cancer, it is an umbrella term. There are many, many different kinds.

There’s hundreds of different kinds of cancer, but now what we’re finding with genomic pathology — taking a look at the genome instead of just cells — is people’s cancer is as individual as they are. So it literally is as many people that will get cancer, that’s how individual cancer is. There’s hundreds of subgroups of cancer and it’s an umbrella term for a whole set of diseases.

The statistic is, during my watch we’ve raised 1 billion, 215 million [dollars] and almost half of it is undesignated, from peer to peer fundraising brands and lotteries. The Ride to Conquer Cancer is the No. 1 peer to peer fundraising brand in the country. We started it and we own it and we loan it out to other cancer organizations. So of the 1 billion 215 million [dollars], about three-quarters of that goes to research. Some of it goes to new technology and clinical care and education. We’re training over 200 fellows, and post-docs a year from around the world, but most of what we fund is research. Because you can treat cancer, but to conquer cancer — because that’s our whole purpose — it’s only through research.

The single biggest idea that I’ve seen come along is called immunotherapy and the simple definition is taking the body’s own immune system to target and fight cancer. We have these T-cells that are the killers cells of our immune system, and viruses and germs and bad things that come into our system, they target them. They know they’re not supposed to be there and they destroy them.

But in our evolution, for some reason, when a cell becomes cancerous, our immune system does not recognize it anymore. Our T-cells are right next to a cancer cell and they don’t recognize it as a bad cell. So what we’re finding is more ways of turning on our immune system to recognize and target cancer. One of the big new stories around this was former President Jimmy Carter had stage 4 melanoma, which was basically an incurable cancer, months from death, and he had one of these new immunotherapy treatments and he’s cancer-free, travelling the world. That is the single most promising thing that I’ve seen.

It’s a really basic idea — our immune system is an absolutely amazing miracle of life and to turn it on to recognize and kill cancer. Interesting thing is our doctor, Tak Mak, who’s here — who’s a total absolute rock star; he’s the Bono of cancer researchers — he did all the discovery work around the T-cell, and he alone has two drugs in clinical trials right now [and one drug in development], that we own all the IP — the pharma companies don’t own; we own it — because we’re able to fund him.

[PMCF note: Thanks to a philanthropic gift in 2015 to support the core functioning of the team, the Therapeutics group has brought two first-in-class drugs from the lab to clinical trial. Our clinical stage drugs inhibit critical enzymes, PLK4 and TTK, that are essential for cancer cells to divide and multiply. The PLK4 inhibitor has now completed Phase 1 trials and has progressed to multiple trials in various cancers including prostate, breast, and leukemias and the TTK inhibitor is in Phase 1. The Therapeutics Group is now developing its first drug in the area of immune-oncology: an inhibitor of HPK1, an enzyme that halts activation of T cells. T cells are a part of the immune system needed to fight cancer within the body. The novel, first-in-class inhibitor of HPK1 developed by the Therapeutics Group has shown significant promise in pre-clinical studies, and is expected to enter human clinical trials in 2018].

Is that unique to own the IP?

It’s unique, yeah. That’s because we raised a lot of money, and our donors don’t want us to give it away to pharma companies. New drug development — there’s all these parallels with the music industry — you have to watch a lot of musicians; you got to kiss a lot of frogs; and then people get signed so few of them actually have hits and tour, and end up turning it into a living. It’s very rare that an artist actually breaks through. The fact that we had three nominees for male vocalist of the year in the Billboard Music Awards — Shawn Mendes, Drake, and [Justin] Bieber, all basically Toronto guys — it’s unbelievable, but, you know what, in cancer research, just around this corner at College and University [where Princess Margaret Cancer Centre is located], not just Tak Mak, we have some of the world’s best researchers in immunotherapy, stem cells, genomics, the real major breakthrough ideas — not the small improvements; the breakthrough ideas for cancer.

You own the research, so you own the treatment and the drugs. You would just hire the pharmaceutical companies to manufacture it?

What we do is take it to proof of concept. You have to go beyond testing in mice to actually testing in humans and that’s called a phase 1 trial. What we try to do is go to phase 1 and then get early evidence, and then to actually develop a drug all the way through phase 3; it’s billions of dollars. We can’t afford to do that, but what you can do is instead of selling an idea or some IP early, you develop it to the point where it’s proven. That’s what we’re doing with the things that we’re developing.

How long would that take?

From the idea, finding a target for a drug to putting in humans, on average 10 years. It’s a long time.

Yeah, absolutely. It is only a matter of time because there’s an exponential increase in our understanding of cancer because of the understanding at the level of the genome, and what’s going on. For example, immunotherapy is such a huge breakthrough idea. Now it’s the earliest stages of how that’s all going to work, but to now with liquid biopsies, with a little of blood, you can look at somebody’s genome and do a diagnosis and turning on our immune system to target and fight cancer cells that are circulating. Totally see that as one of the huge ideas and it’s already here.

Why can Jimmy Carter get that treatment and others can’t?

These are trials. These aren’t available widely. One of the things that distinguishes Princess Margaret, 1 in 5 patients are on a drug trial, so 20 percent versus at a major cancer centre in the U.S. about 5 percent, and again the Foundation funds all those. The thing about trials is not everybody who thinks they can use the drug can get them because it’s usually limited depending on whether it is phase one, two or three.

We’ve all seen the panic that sets in with a cancer diagnoses, especially stage 4. Loved ones start researching. Patients go to Mexico, to Europe, to get a special treatment; at home some go organic and replace all their non-stick cookware with non-toxic. They try anything and everything. From your viewpoint, and all that you’ve learned the past 14 years, is that a waste?

Being hopeful is always good.

It’s also very costly.

Yeah, shark cartilage and all this stuff. There’s so much false hope that’s sold to people. You really want to pay attention to the hard science. There are so many places in Mexico or even in Europe that promise you treatment, that cost a lot of money and will do no good for you. There is so much research going on to things that actually do work and there are naturally occurring remedies for cancer. There are things that we’re seeing in the natural world. We have a joint venture in Shanghai and one of the reasons is it’s very advanced in looking at trace elements in all kinds of naturally occurring items, like green tea. Is green tea going to cure your cancer? No, but trace elements in green tea, as we understand them, that could be really effective in different ways at stimulating your immune system, and other things, like red wine. A lot of cancer does relate to lifestyle so smoking, too much sun, being overweight, being sedentary. There’s a lot of very healthy vegan-run marathons. There’s no guarantee.

Has there been any studies on vegans and cancer?

I don’t know about that. There are lifestyle issues. Smoking is No. 1; too much sun, obesity, high fat foods. These are lifestyle things that predispose you to getting cancer, but there are also people that are 104 years old that smoke and drink every day that don’t get cancer, which is part of what we want to understand.

A healthy lifestyle, 10,000 steps a day, walking, those basic things, these are all very preventative. The benefits for men of eating tomatoes, stewed tomatoes in particular for prostate cancer. Prostate cancer is lower in the Mediterranean because they eat a lot of tomato sauce and stewed tomatoes. When you cook a tomato, it releases these things that are very good for you, but you have to eat that diet your whole life. You just can’t start eating 20 tomatoes a day. It is a healthy lifestyle over a long period of time.

Now to what you’re being celebrated for, raising all this money, more than $1 billion. Obviously, many foundations and charities would like to raise a billion or even a million dollars. People are asked to give money all the time. What are the key steps for any fundraiser, big or small?

I’ve never told anybody this but I’ll tell you, I actually have never worked as a fundraiser for a day in my life. I don’t consider myself a fundraiser. I don’t see myself as part of the fundraising community, but I’ve managed to raise $1.2 billion for cancer in Canada. And the reason for that is I have absolutely a burning desire and passion to try and do something important for cancer. If you’re raising money, you have to have authentic passion for your cause. Going out and asking people for money, if you don’t have that, people see it; they read it. A lot of people are harassed; you get inundated with requests for money. There’s a lot of well-meaning organizations, but everybody gets asked for money all the time. People who have a lot of money, they are absolutely under siege with requests. So having a really authentic passion for what you’re doing, that translates; if you have that, then you’ll be so much more successful in securing funding.

There’s two things. There’s passion for the cause and its impact. You’ve got to be able to say to people — if its 10 bucks, 100 bucks, 1000 bucks, or 50 million — here’s the impact of what you’re doing.

One of the things that has really helped drive our success is we have 1200 researchers at our research tower, and then next door we have 1 million square feet, another 2000 people, that are clinicians and nurses and healthcare workers. If you give us money, then we say, ‘Here are the people that are using your money. Meet with them. Hear from them.’ And we do it on a regular basis, six months every year. Even people who give relatively small amounts of money, we have special events where the doctors come out and they speak and there’s always a Q&A, and then face time.

And what’s so interesting is when people get money and trust, they know they gotta face up to the people that gave them the money, so they better have answers. There’s a lot of pressure on the people who get money. We don’t collect the money and, in a faceless, nameless group of people, push it out to what we think are well-deserving people. We say, ‘Hey, Karen, give us 100 bucks, I’ll introduce you to Tak Mak, and he’ll tell you why immunotherapy is going to be a cure for glioblastoma or why he thinks that he’s got an idea,’ and then you decide if you want to give him 100 bucks, and then six months from then, he’ll say, ‘I tried this; it’s not working’ or ‘This is working’ or ‘This is the result.’ Showing people the impact of the money, that’s what success is all about. So few organizations have that kind of transparency. It’s like face to face with the people using the money.

What don’t you like about the word ‘fundraiser’?

It’s not that I don’t like it. It’s just I’ve never seen myself as a fundraiser. I raised money, but the book I wrote about passion capital, that financial and human and intellectual capital all follows people with enormous passion for what they’re doing, that’s what I do here. Every day, I get to work with people that inspire me, and what I have to do is try to find people that have the means and they have a cancer story. If you don’t have a cancer story, you’re not going to support us, but if you do, if you’re treated at Princess Margaret, we have researchers that over the last seven or eight years we’ve been in the top 5 in our research performance. Citations and high-impact journalists are our measures — the most important discoveries, and that’s in the world. This place, down at College and University, people from around the world want to come here because of immunotherapy, our stem cell research, and other things that we’re doing.

And the single-payer system, our Canadian healthcare system, gets a lot of grief about all its frailty, but there are things that it’s really good at. When people get cancer and you get sick, you’re gonna get looked after even if it’s gonna take time, where in the U.S., we have friends down there that say when someone gets cancer they can’t even afford the costs of tests let alone treatment; the person just dies. There is a real benefit to the Canadian healthcare system to help drive research too because we can capture data much more effectively than the individual cancer centres that all compete with each other in the U.S.

How did you go from working in the music industry — a fun job where listening to music and going to concerts is a requirement — to this? It’s very different.

Stuart McAllister, the chairman of HMV — he died of cancer by the way, my great mentor and friend in my career — he hired me at aged 33 with no retail experience and no music experience. I think what he saw is that I have enormous passion for music, I play a clarinet very badly, but as most of us know on the business side of the music industry, to really succeed you have to love it, or else you won’t do it. I found at HMV, getting a like-minded group of people together, and really being passionate about introducing music to people, this was our job in life. If we did it better than anybody else, we’d build relationships with people who love music and buy it, and you’d be successful. What I’m doing here, it’s the same thing. It’s just my passion shifted.

When my mom died of cancer, her request was, ‘I want to be at home. I don’t want to be in a hospital.’ She was the glue in our family and just absolutely an amazing person, so we (my brothers and sisters and I) signed up for that, but we had no idea what we were signing up for. We had never seen anyone die of cancer. The last three months — in our home we had a hospital bed and we set it up in our sunroom — we had no idea how difficult that was going to be, and it changed all of us.

I never thought I’d be working in a hospital. I played football my whole life and I almost faint when I get flu shot. Giving blood is one of the biggest sacrifices in the world, a little pinprick. Working in a hospital, are you kidding? But when my neighbour across the street, John MacNaughton, who was a board chair here, I was telling him about this experience with cancer, he said, ‘You gotta come in.’ As soon as I met the people, the scientists and the great docs, it’s unbelievable how similar they are to really talented musicians, singer-songwriters, performers. There is some big connection in their DNA, and, yeah, they’re really smart and talented and creative and all those things, but great musicians and great doctors and researchers, they’re the same people, in so many ways.

I came in and I met these people and it’s like, ‘Oh my god, I could do something here.’ So the first year working in a healthcare system, I was running into the side of a brick wall, working in publicly funded healthcare, are you kidding? And I had one of those decision points, I’m either gonna quit because I can’t do this or this is the only thing I can do and I’m going to make it work. What I started to see was I learned my way around the healthcare system, and the relationships and the way things work, just like the music industry when I came in the first year not knowing anything or anybody. Sam Sniderman [founder of competitor Sam The Record Man record retail chain] was like, ‘He’s gonna be gone in a year and he’s gonna fail.’ [laughs]

Did you take anything from heading the music companies to this environment?

Totally. Your job is to translate your passion or music, or translate your passion to try to conquer cancer, translate that to other people and bring in a group of people and build a culture that works, a performance-based culture. The average tenure here is eight years. Most fundraisers come in and spin every two years. People come here and they stay. Three times we’ve been recognized as one of Canada’s most admired corporate cultures [for the broader public sector in 2016, 2013, 2010 by Waterstone Human Capital]. To raise that amount of money with 70 people, that is a small staff to raise over $100 million in fundraising every year. So the culture of how people work together and treat each other, that’s a super important part of what happened at HMV, and that’s what I learned and brought here.

What happens with the money that is raised through the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre Home Lotteries?

The two Princess Margaret real estate home lotteries are the largest single source of funding for cancer research in Canada. We pay 1200 of the world’s best researchers because we’re really good selling lottery tickets. Is that a good thing? Should we proud of that, as Canadians, with all the money we spend on research and healthcare? I have two P&G [Procter & Gamble] trained MBAs here who work with me; we are a package goods marketing machine here with our lotteries. We raise $30 million in net fundraising from our lotteries. That pays all the salaries, all the technology, rent, overheads, the whole building for our research enterprise. So our lotteries are so important. If we don’t sell all our lotteries, our whole research enterprise is hugely at risk. Is that a good thing that we should be proud of? I don’t really think so. I don’t think we should support one of the world’s great cancer centres because we’re really good at selling lottery tickets.

For our board, and one of the biggest concerns they have, not just the lotteries, but $100 million a year, $10 million goes into the genomic screening program. We pay for all the genomic tests that go in. Now, it’s about $1000 a patient. It’s not huge amounts of money, but then there’s all the care. Understanding somebody’s cancer at the level of their genome is very different than looking at blood cells or tissue cells. So we go from looking at cells to looking at the genome, and the genome gives you so specific information on the person’s cancer. We’re doing that in this country. You can go to the top cancer centres in the U.S. and pay five or 10 grand just for the test; we’re paying for all of it, 10 million bucks a year; the Province [of Ontario] is paying for zero. This is the standard of care at the best cancer centres of the world.

Do you see that changing with the Province?

Yeah. We are presenting to the Province. Not only is doing genomic pathology, and understanding cancer at the level of the genome, way better for the patient, but it’s cheaper. Like we can do one of these $500 or $1000 tests, and find out if somebody’s going to benefit from $150,000 stem cell transplant or not, or will benefit from a cancer drug that might cost $10,000 or $20,000 a month or not. Why put someone through chemo — because a lot of chemo drugs, we think that they work on your particular type of cancer, but what we understand more and more now, is cancer is so individual that certain chemo drugs that we think work for lung cancer, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, they don’t work on you at all even if you have lung cancer, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer.

So the lotteries; the walk [Rexall OneWalk To Conquer Cancer] that we do is in its 15th year; the Ride To Conquer Cancer has raised $168 million in 10 years; last year it raised $20.5 million. But going back to one of my earlier points about impact, we have 150 doctors and surgeons who do that ride. So wherever you are, you’re not far away from somebody who is using the money. So many conversations are about ‘What’s going on?’ ‘Is robotic surgery really better for prostate cancer or gynecologic cancer surgery?’ You hear all these conversations going on.

And to raise 20 million bucks a year in an event, well it’s the No. 1 peer to peer fundraising event in the country. All the staff here, we do the ride [200km from Toronto to Niagara]; we do the walks. In the music business, you think you go out to a lot of concerts? We have 150 events a year.

Speaking of what’s not covered by our healthcare system: dental care which is costly and can lead to all kind of medical problems. Can an abscessed tooth lead to cancer?

Infections don’t really lead to cancer. If you smoke or if you drink, then the chances of getting mouth cancer, throat cancer, stomach cancer are much higher. So it’s all about what you put in your mouth, but we have Canada’s only dental clinic for cancer patients because head and neck cancers — we have eight surgeons — and the world’s largest head and neck surgical program. If you get radiation treatment, then you generally are gonna often have lots of problems with your jaw and teeth, and a regular dentist doesn’t know how to treat you. So we have five dentists that just work on cancer patients. But good hygiene and good health is generally not a guarantee you won’t get cancer.

You did build the same-day diagnostic centre for breast cancer at Princess Margaret [Gattuso Rapid Diagnostic Centre]. Is that possible for other cancers?

Thanks mainly to [funding from] Emmanuelle Gattuso and Allan Slaight, and Gary and Donna Slaight, as well. Emmanuelle is a breast cancer patient. She helped drive that whole thing with David McCready, who was her breast cancer surgeon. She said to him, ‘Why would it takes six or eight weeks to get a diagnosis and find out what’s going on?’ So they did this big donation of $25 million dollars [in 2009] and we built the Gattuso Rapid Diagnostic Centre [which provides one-day diagnoses and treatment plans to breast cancer patients].

We are using rapid diagnosis protocols and standard operating procedures developed through the Gattuso Rapid Diagnostic program in lung cancer and pancreatic cancer. We have a centre established in pancreatic cancer, the [Wallace] McCain Centre. We do not have a named centre in lung cancer, but are using some of the protocols and procedures learned from the Gattuso Centre in lung cancers. [Rapid diagnosis is also now being embraced by other cancer sites, including colorectal and prostate cancers].

Being diagnosed early is one of the most important things for a successful outcome. We have public healthcare. If you have lumps and bumps or if you are worried, go to your doc right away. The basic stuff, getting a mammogram, PSA [prostate specific antigen], colonoscopy, are not the most pleasant things in the world, but it’s real simple stuff.

Sometimes catching cancer early is tough for people who don’t go running to the doctor. You can go because you have a bad cough; they tell you it’s only a cough; it persists, you return months later, then eventually you get diagnosed with lung cancer and it can be stage 4 by then. Is it too costly for your family doctor to just go, ‘Oh, you have a cough; let’s check you for lung cancer?’

You can’t do that with everybody who comes in with a cough, but for a lot of basic physicals you can get a chest x-ray. There might be a cost, but it’s like $25 or something, and a simple blood test can show a lot of things early on.

What will be happening, in the next five years, is there are companies like 23 And Me that are offering genomic-based information. The FDA in the U.S. is being very cautious, but our genome — in the technology to read our genome, not just about cancer — tells the story of what’s going on with our health. A simple blood test right now is unbelievably helpful, and PSA for guys, mammogram, chest x-ray, if you’re worried, those aren’t difficult things to arrange.

Early diagnosis, if you’re worried, if you have cancer in your family, you should be really aware, and the smoking, drinking, too much sun. Just be really aware. If you’ve been in the sun way too much, you get spots and bumps, then have your doc check them out.

Well 14 years and 3 months. It’s been a long wonderful tenure. But this job, there’s the $100 million a year of that fundraising, which is challenging, but the whole world of being surrounded with people with cancer all day, it’s just really hard, to be honest. After 14 years, I really need a break from it. As much as I have so much passion to try and do something for it, it’s just like, oh, man, I have so many friends now, and people that I’ve got to know well, that have cancer, and I gotta have a break from it.

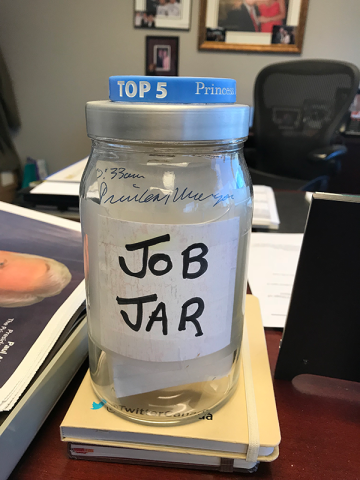

You hit your target from the job jar.

That’s my job jar right there [on his desk with just one piece of paper inside]. It’s not bullshit. There it is. Raise a $1 billion. And I got my bobblehead to prove it.

A two-thumbs up bobblehead.

Absolutely. It’s my Don Cherry two-thumbs up.

So no plans? You’re just going to enjoy life?

I’m gonna take six months off, and then I’ve never really planned my career, it’s serendipity, so we’ll see. I don’t know if I’ll go back to work full-time or if I’ll work for a for-profit or not-for-profit. I don’t know.

There will also be a meeting/conference room in the Foundation’s space in the Cancer Centre named after you, once it is renovated.

You see all the construction work going on in the hospital. It’s on the ground floor.

That’s pretty cool, it’s going to be named after you.

That’s very cool. I’m very honoured, but the bobblehead is still the coolest thing.