Back then, the singer-songwriter, born on the Piapot Cree First Nations Reserve in Qu’Appelle Valley, Saskatchewan, was named Billboard magazine’s Best New Artist. Two of those early songs, the war condemnation “Universal Soldier” and addiction confessional “Cod’ine” became folk classics, the former covered by everyone from Donovan to Chumbawamba and Jake Bugg; the latter also by Donovan, Janis Joplin and Courtney Love. “Now That the Buffalo’s Gone,” about the confiscation of Indian lands, includes the lines “Oh, it’s all in the past you can say / But it’s still going on here today,” and decades later she is still writing about Aboriginal issues.

The topics don’t really change on Power in the Blood — war, government greed, Native rights and respect. Samaritanmag talks with Sainte-Marie about them all, and more.

You’ve had over 50 years of activism! And in your music too. Some artists like Bryan Adams — who just got a humanitarian award — is an interesting case because he’s so socially aware and such a big humanitarian but he made one album only that addressed political and social issues and then kept those views out of his music. Why is it important for you to do both? You have love songs and social activism or criticisms.

“Well thanks for recognizing both. And there’s a lot in between those two extremes. But it all just comes naturally to me. If a song pops into my head, who am I to send it away? So the kind of writer I am, it’s like if you go to sleep at night you don’t know if you’re going to dream. And you couldn’t possibly figure out what you’re going to dream. So songs have come to me — they still come to me in the same way— and they’re about everything. They’re about happy things and sad things and everything in between. So I’ve always written about the countryside, like ‘Piney Wood Hills’ and the ‘Farm in the Middle of Nowhere,’ but I’ve always written about hard things like ‘Power in the Blood,’ ‘Universal Soldier,’ and love songs too. But you work on them differently. It’s a different process. Because I can have something like ‘Universal Soldier’ pop into my head as a big idea, but then I sit down and, unlike a love song, I’ll work on it because I want really to give it to other people intact. And I feel as though the art of a three-minute song is a great skill.”

It a skill to distill down a complicated issue that people write books on, make documentaries on, lecture about and make their life’s work. And you take this issue and put it into three or four minutes.

"Well, you want to use that three or four minutes not just to make a lot of noise and have it be a pretty song, no. You want to be effective in helping the listener understand what the point is, and hopefully be able to see it in a new way and make an informed decision about something they don’t usually think about.”

Was there a song early in your career that you felt and saw could make a difference and did make a difference?

“Oh yeah, immediately. Immediately. I graduated college and I had a teacher’s degree and a degree in Oriental Philosophy and I thought I was on the way to India. I didn’t know I was going to become a famous singer right out of the box and be rich and famous by the time I was 24 (laughs).

“I didn’t know any of that. So I gave it a shot in Greenwich Village. I gave it a shot. I was singing songs that I had sung to the girls in my dorm and a little off-campus coffee house. And I sang things like ‘Now That the Buffalo’s Gone’ and ‘Universal Soldier.” And, to me, these songs were just natural outgrowth of the life I was living.

“In the 60s students ruled, and there were kids all over the streets who had figured out that not only did they not want to go to somebody’s damn war, but also that anybody could play the guitar (laughs); you don’t have to go to music school! So there were a lot of people sharing their views and I was just one more. I was just writing about what I knew about. Number one, ‘Universal Soldier’ was a universal theme — everybody has to deal with the fact that the suits will send you to war maybe. That’s just the war racket. That’s just how it is. But ‘Now That the Buffalo’s Gone’ was totally different; it was reaching people with information that they’d never even though about because it was about Aboriginal things, and it was the first time people had got Indian 101, in three minutes.”

WATCH A 1970 PERFORMANCE OF "UNIVERSAL SOLDIER":

It’s interesting that you say that because I can't say I regret that I never learned about Native culture and history in junior or high school because we just didn’t have it to learn, right? — but I wish we did.

“Well neither did Native people! Nobody got to know about it!”

I went to the Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, and really, it’s the history of racism – it’s a crash course. It’s done chronologically, and when I left, not that I didn’t know all those things, but it really crystalized for me why there’s such a disparity between the whites and the blacks, and I wish there was a dedicated Native museum — not about the artifacts but the history, where I could see what we’ve done to such a beautiful culture and community in North America, and learn more and understand.

“Well, a propos of your first question, do the songs make a difference? I’m told that they do. ‘Now That The Buffalo’s Gone' really informed people immediately. And a lot of people stood up and took notice. Because the times were right for that — people’s ears were open. I think partly because of coffee houses. I mean, the folk music, and all of those movements, they started based in coffee houses, which were gathering places for students. There was no alcohol; it was just talk talk talk, listen listen listen — listen to each other’s music, the music of other cultures. Everybody was into it. Everybody was real curious about it. It was kind of like the internet is now.

“But ‘Universal Soldier,’ a couple of years ago, if you go to my website you can see the exact stuff that I said about it, but just to encapsulate what’s already on the website, Smithsonian magazine did a story on Vietnam War soldiers who had written and carved things into their bunks and duffle bags and stuff like that. And they did a story on this one guy who had carved in something like, ‘the one who gives his body as a weapon to war’ and they said it was anonymous, yeah? They said it was anonymous. Oh, they got over 700 letters, emails, faxes from people saying, ‘Oh, that’s from ‘Universal Soldier.’

“And they called me up all embarrassed, I wasn’t aware of it, and they said, ‘Would you like these big bundles of mail?’ (laughs) and I said, ‘Yeah!” so they sent them to me. And a lot of them were very poignant messages from soldiers who had understood war for the first time because of that song. Or draft dodgers who had come to Canada. Or women who realized that it’s not only men who are responsible for the world we live in, in terms of war, but it’s us who encourage our sons, our lovers, our brothers, to go and kill somebody for somebody else.

“I’m always a bit taken aback when people say, ‘Buffy, you’re such a warrior for peace.’ That just makes my hair stand on end because I’m not a warrior. And I always try and correct people in a nice way. Because a warrior is a very specific word and I think it ought to be reserved for veterans and actual soldiers. But I’m not a warrior. I’m not willing to go to war. I’m not going to go and kill somebody for any reason, so what I say is that I advocate for alternative conflict resolution. And that’s different. It’s different from being a warrior and it’s different than peace. Peace is different.”

I read that. It’s in your liner notes, where you say ‘what I represent is new thinking about alternative conflict resolution’. So what is that alternative conflict resolution?

“Alternative conflict resolution is what we don’t have. In North America, we have five heavily funded colleges of war. And a military officer can go and get advanced degrees in making war. He can go to the army college of war [US Army War College], to West Point [United States Military Academy], to Annapolis to the Royal Military Academy [United States Naval Academy], to the Air Force Academy, and get a degree in making war better. And we don’t have one college, all these years later — as proud as I am of my generation — with that kind of seriousness, funding or clout that will teach people about alternative conflict resolution.

“And we’ve had racketeers around since before the Old Testament, but we’ve always had people around like Jesus, like Martin Luther King, like Gandhi, really effective people in alternative conflict resolution, and it’s such a good thing! We really need to be teaching each other about it, and it can be taught! But usually if it’s taught at all it’s one course at a college. There are no colleges really dedicated to it. So maybe in another 30 years, we’ll have that.”

“Yeah. The Cradleboard Teaching Project is the main initiative of the Nihewan Foundation. I founded the Nihewan Foundation in 1968 or ‘69, to give scholarships to Aboriginal people who had no idea how to negotiate the path between high school and how to get to college. They just didn’t have the money. They were not connected to business people, to lawyers, to foundations. They didn’t know what the Ford Foundation was! So I started my own foundation and it required people to apply to other foundations first, and if they were turned down twice then they could get a Foundation scholarship for my foundation.

“So over the years, I developed it into a K-12 and then teacher education program, called the Cradleboard Teaching Project. Right now the classroom partnerships are not happening. I’m working privately with a number of colleges, going to teacher education departments of colleges and teaching them how to write their own interactive multimedia Aboriginal curriculum — in science, geography, social studies, government.

“People always think, ‘Oh, it’s got to be about beads and feathers and here’s where the Navajos live, and there where the Sioux live, and the history of how the white man screwed the Indian.’ But that’s not what it is. Science through Native America eyes, people will say, ‘Oh, that’s impossible. Indians didn’t have science,’ but anybody who has survived has survived because of the principles of science, of observing and knowing that, okay, if the berries are ripening, you know that pretty soon something else is going to be happening in nature. It’s not the same as looking up at the stars and saying, ‘Oh, there’s a buffalo in the sky. That means the buffalo are coming.’ No, see, it’s two different things.

“So it was a very successful project. We gave away over $2 million to local teachers, educators, students, people who were writing curriculum. So what we do now is we work with teacher education programs and teach them how to do what we were doing, but making it locally relevant to their own people.”

Is this just in America or in Canada?

“It’s only in Canada at the moment.”

It’s come to our attention because of the internet that in remote areas of northern Canada, people have to pay $100 for a 24-pack of bottled water, $28 for a cabbage. Have you seen these reports and photos with the price tags on the products?

“I’m not surprised. Racketeering is just raging right now."

People across Canada — where food costs are reasonable — have been organizing food drives to ship containers to families there.

“It’s always been hard in remote communities. It’s one of the big problems. It’s very shocking! But it’s just another way for racketeers to drain money out of people, in this case Aboriginal people. But that’s not new! I remember at Piapot, Saskatchewan, my reserve, in the 60s, there wasn’t any water. You had to get water from the river. So when people went to town, they’d bring back Coca-Cola and beer. Both were really bad for kids. And yet that’s what there was. And nobody was telling anyone that there was anything wrong with that. And it was very expensive. If you were to study Indian history, you’d find a lot of cases where, for instance, the Sioux Uprising in Minnesota happened because the Indian agent who was getting government funding to provide rations for Aboriginal people who had signed away their land, expecting those rations to happen, the rations were not delivered. Or they’d give them a little bit. Or the flour would all be moldy. It’s just classic. It happens a lot. It’s marginalized people and racketeers, and the people in between don’t really know what’s going on. I mean you wouldn’t know and I wouldn’t know.”

“Exactly. But it was still going on. Exactly. I think we’re both on the same trail here. And in the 60s, it was like that. In the 60s, the cat was out of the bag. We weren’t going to the damn war. We could self-publish our own opinions and facts. We were telling each other what was going on in the world. Then for about 40 years everything just got really corporatized, and people no longer had that access to media that we had before. Music turned into The Mamas & the Papas, really mild. If it was protest, it was like Crosby, Stills & Nash kind of protest. It was no longer Phil Ochs and Bob Dylan’s ‘Masters of War.’ It wasn’t like that any more. That all went away.

“But now with the Internet, people are self-publishing and letting others know what’s going on, so that’s real good. The problems are not solved, but what is really good is the problems are more visible than ever. They’ve been there all along. And for me it’s interesting because I remember saying in the 60s, ‘This is happening to us now, but pretty soon the same racketeers who bleed us, who oppress us, will be bleeding and oppressing you.’ And now that day has come. Okay, so that sucks. But what’s good is that more people than ever are aware of it, so more people than ever can help to solve it. So that’s good. And every day, I find something that makes me mad and something that makes me glad. And that’s always good, if you can be like that.”

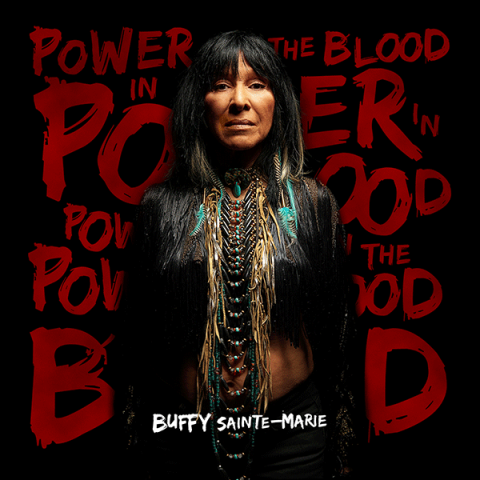

Let me ask you about some of the social critiques on your new album and your inspiration for them, starting with the title-track, Power in the Blood, your spin on Alabama 3’s song.

“’Power in the Blood’ was originally — if you listen to A3’s version, which I do advise — it’s wonderful but it’s a violent song. It’s a song about violence, but I turned it into a peace song. So they were – ‘I will raise mah sword upright’ and ‘the blood of the unredeemed’ – I mean it’s really bloody. But I loved it. I love the drive of the song. So I asked them and they laughed at me, ‘ Oh, it’d make a great peace song!’ But I sent it to them and they loved it, and I love it. It’s a nice collaboration in that the energy for the music is coming from them and my band, but the intelligence, the information of the lyrics, is coming from my life and what I see, which is a different perspective.”

Is it a shame that 50 years later you’re still writing an antiwar song?

“Yeah, in a way, I guess. But the war racket being what it is – you know, the First World War was supposed to be the war to end all wars. So was the Second World War. So was the Vietnam War, right? But people just keep on going to sleep. We elect politicians and then we don’t follow through. We give them the key to the mint and then we expect them not to steal and reroute things. We give them the clout, but then we don’t stay in the position to influence them. We go to sleep on it! So that’s the mistake we make. And we don’t have to make that mistake any more. I think we’re finding that out more than ever.”

Tell me about the song “Uranium War.”

“It’s kind of a prequel to [1992’s] ‘Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee.’ The song is true. The people are true. And it’s a song that I’ve had for a long time and never felt like recording, and I just felt like recording it now. [Murdered Mi’kmaq activist] Annie Mae Aquash is mentioned in both ‘Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee’ and this one, so I dedicate it to her family.

“Corporate greed kills people (laughs)! Corporate greed colludes with political administrations and Indian people are wiped out, marginalized people are exterminated, and nobody hears about it for 30 years.”

‘Sing Our Own Song’ is a UB40 song from the 80s that you have modified.

“Oh that was a great song! Geoff Kulawick from True North [Records] brought me that. I asked him, ‘Aren’t there any songs with meaning out there?’ And I thought maybe I’d get to hear some new writers, but Geoff brought me that and a few others, and I liked it a lot. UB40 wrote it at the time of Nelson Mandela and the anti-apartheid movement. So I heard it and I loved it, but I wanted to make it relevant to today and to First Nations people. And so I asked permission from Northern Cree, who are my own favourite powwow group and I sampled some of their records, so they’re the singers on it, and we backed them up.”

Some songwriters are really protective of their songs. Some wouldn’t let another artist change lyrics. Obviously Alabama 3 and UB40 have great respect for you.

“Well, also, I didn’t have some lawyer going in and saying, ‘Well, we’re going to take part of your publishing money because I would never do that. I gave up the publishing for ‘Universal Soldier’ for $1. But when Elvis Presley’s people wanted part of publishing on ‘Until It’s Time For You to Go,’ I said, ‘No,’ — and I don’t do that to other writers. So number one, and number two, with ‘Sing Our Own Song’ and ‘Power in the Blood,’ I didn’t ask for one penny. I said, ‘Absolutely not. No.’”

And finally, “Generation,” from 1974, that is on Power in the Blood.

“’Generation’ is a song that I wrote at a time that I was trying to get to the Rosebud Sioux reservation for the sun dance. And I was in Regina wandering around town with my dad — and it was when they were trying to put the man on the moon — and he said, ‘They ought to leave that moon alone’ (laughs). So it was really quite early for anybody to be saying things like, ‘goodbye banker’s trust,’ but as a global person, sometimes I get to see things in a way that local people who only live in one city, they think it’s only happening in their city but I say, ‘No, this is happening.’ The whole idea of bankers and what we see as corruption, that’s only come about in the last few years, that local people can see what’s going on globally, but a lot of us could see it way before. So ‘Generation’ is about it’s really about being inspired in hard times, including kids. ‘Kids were sent from heaven inside to lead you to the future / Wrap their eyes in blindfolds and still they’ll find their way.’ In spite of what adults are doing wrong, kids are always the new future and maybe can get it a little more right.